Catching Parkinsons Early: What You Need to Know

Parkinson’s disease is often misunderstood as a condition that only causes tremors in the elderly. But in truth, the disease can begin subtly — years before the hallmark symptoms emerge. Recognizing early Parkinson’s disease (PD) can be life-changing, helping individuals seek care, prepare for the future, and begin treatments that may ease symptoms and delay progression.

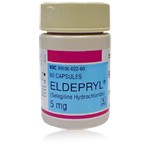

This article explores the nature of early Parkinson’s, including how and when it starts, what the first signs might look like, what “Stage 1” means, whether early detection helps, and the role of medications like Eldepryl (selegiline) in the initial stages of treatment.

What Is Early Parkinson’s Disease?

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive disorder of the central nervous system. It primarily affects dopaminergic neurons in a region of the brain called the substantia nigra. As these neurons deteriorate, the brain produces less dopamine, a neurotransmitter critical for smooth and coordinated movement. This decline is gradual but relentless.

When we talk about “early Parkinson’s,” we refer to the initial stage of the disease — typically the first 2–3 years after diagnosis, when symptoms are relatively mild. During this phase, individuals may still carry on most daily activities without major interference. For some, the signs are so subtle that they are attributed to aging, stress, or other unrelated issues.

Many people don’t realize that Parkinson’s symptoms may start years before diagnosis. Non-motor symptoms such as constipation, depression, or sleep disturbances often appear before movement-related signs. These early features are called “prodromal symptoms” and are important clues that Parkinson’s disease is developing.

What Are the 5 Early Signs of Parkinson’s Disease?

Although everyone’s experience with Parkinson’s is different, several early warning signs tend to appear in the beginning:

- Loss of Smell (Hyposmia or Anosmia) A reduced sense of smell is one of the earliest and most overlooked signs. Many people experience a dulling of their ability to detect odors such as coffee, perfume, or spices. Because this sign can develop years before other symptoms, it’s often dismissed until a Parkinson’s diagnosis connects the dots.

- Constipation Digestive changes — especially constipation — can signal the disease’s presence in the autonomic nervous system. The nerves that regulate bowel movements become less efficient, slowing digestion. Constipation is so common in early Parkinson’s that it is considered a red flag by many neurologists.

- REM Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD) RBD involves acting out dreams while asleep. Affected individuals may shout, kick, punch, or even fall out of bed. It’s not just a quirky sleep issue—it may be a strong predictor of neurodegenerative disease. Studies show that many people with RBD go on to develop Parkinson’s or related disorders within a decade.

- Micrographia (Small Handwriting) A gradual shrinking of handwriting, where letters become small and crowded together, is often noted by patients or their families. It reflects the bradykinesia (slowness of movement) associated with Parkinson’s.

- Changes in Walking or Movement People may begin to move more slowly or notice a reduction in arm swing on one side while walking. Others may shuffle slightly or feel that one side of their body is “stiff” or “dragging”.

These signs may seem minor at first. Yet, when several occur together — especially with family history or other risk factors — they merit evaluation by a neurologist.

Can You Stop Parkinson’s If Caught Early?

The short answer is no — Parkinson’s cannot currently be stopped or reversed. Once the neurodegenerative process has begun, it continues. However, catching it early can still make a meaningful difference.

Here’s why early diagnosis matters:

- Symptom management is more effective when therapy begins before severe impairment.

- Early intervention helps maintain independence and quality of life.

- It gives people time to plan ahead—financially, socially, and medically.

- Clinical trials for potential disease-modifying therapies often target people in early stages.

While we don’t yet have a treatment that halts progression, a combination of medications, lifestyle strategies, and therapy can significantly delay disability. The earlier this support begins, the better the long-term outcomes.

Some scientists are investigating whether aggressive early treatment could slow degeneration. However, much more research is needed to confirm this approach.

What Is Stage 1 of Parkinson’s Disease?

Parkinson’s disease progression is often described using the Hoehn and Yahr scale, which divides the disease into 5 stages:

- Stage 1: Mild symptoms affecting only one side of the body.

- Stage 2: Symptoms on both sides, but without balance problems.

- Stage 3: Loss of balance and some disability, but still fully independent.

- Stage 4: Severe disability; the person may need help with daily tasks.

- Stage 5: Advanced disease requiring a wheelchair or full-time care.

In Stage 1, people often remain highly functional. They may notice stiffness, tremor, or slowness in one hand or foot. For example, a person might drag their right foot or have difficulty with fine motor skills like buttoning a shirt. Others may notice reduced facial expressions or quiet speech.

Because symptoms are subtle and only affect one side, Stage 1 is often overlooked or misdiagnosed. Yet it’s the best time to begin therapy and adopt lifestyle changes that may slow progression.

What Age Does Early Parkinson’s Start?

The average age of Parkinson’s diagnosis is about 60. But for many, symptoms begin gradually in the years before this. A significant number of people experience early signs in their 50s and may be diagnosed shortly thereafter.

Some individuals develop what’s called early-onset Parkinson’s, which typically means symptoms begin before age 50. This group makes up roughly 5–10% of Parkinson’s patients. These younger individuals often face unique challenges — they may still be working, raising families, and not yet eligible for retirement or disability services.

Even rarer are cases of juvenile Parkinsonism, which can occur before age 20, often due to genetic mutations. These cases are extremely uncommon.

Age of onset matters because younger patients typically live longer with the disease, and treatment strategies may differ based on age and lifestyle needs.

The Role of Eldepryl (Selegiline) in Early Treatment

One of the medications sometimes used in early Parkinson’s disease is Eldepryl, the brand name for selegiline. This drug belongs to a class called MAO-B inhibitors, which block an enzyme that breaks down dopamine in the brain.

Since Parkinson’s involves a shortage of dopamine, blocking its breakdown helps increase levels of this key neurotransmitter. Here’s how Eldepryl plays a role:

How Eldepryl Works

Selegiline inhibits monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B), the enzyme responsible for degrading dopamine. By slowing this process, the drug helps make more dopamine available for brain signaling. This doesn’t create new dopamine but helps the brain use its remaining supply more effectively.

Benefits in Early Parkinson’s

In the early stages, when the brain still produces some dopamine, Eldepryl can offer mild symptom relief and potentially delay the need for stronger medications like levodopa.

Some studies suggest that starting selegiline early may delay the onset of disability and reduce the need for levodopa by up to a year. This delay is helpful, as long-term levodopa use may eventually lead to motor complications like dyskinesias (involuntary movements).

Side Effects and Considerations

Eldepryl is generally well tolerated. However, it can sometimes cause insomnia, especially if taken late in the day. It may also interact with certain antidepressants or foods high in tyramine (though this is less of an issue at normal doses).

Modern practice often favors rasagiline, a newer MAO-B inhibitor with a similar mechanism but better tolerability in some patients. Still, Eldepryl remains a valid option for early treatment and is especially useful for patients who want to delay stronger drugs.

Lifestyle and Supportive Strategies

While medications play a crucial role, they’re not the whole story. People in the early stages of Parkinson’s benefit greatly from:

- Regular aerobic exercise (walking, swimming, cycling)

- Physical and occupational therapy

- Speech therapy for those with soft speech or swallowing issues

- Healthy diet rich in fiber and antioxidants

- Mental health support, especially for depression or anxiety

- Support groups for emotional and social well-being

Staying active both physically and socially is associated with better outcomes. People who exercise regularly often experience slower symptom progression and improved quality of life.

Conclusion: Why Early Detection Matters

Parkinson’s disease doesn’t begin with a dramatic tremor. It starts quietly — perhaps with a fading sense of smell or a stiff shoulder. But by recognizing these signs early, individuals can seek help, begin therapy, and take control of their future.

While we don’t yet have a cure, the tools we do have — from medications like Eldepryl to physical activity and nutritional strategies — are most powerful when used early.

If you or someone you know is experiencing signs that might suggest early Parkinson’s disease, don’t wait. Talk to a neurologist. The earlier you take action, the more choices and control you’ll have over the journey ahead.

Drug Description Sources: U.S. National Library of Medicine, Drugs.com, WebMD, Mayo Clinic, RxList.

Reviewed and Referenced By:

Dr. Michael S. Okun, MD Professor and Chair of Neurology, University of Florida. National Medical Director of the Parkinson’s Foundation. Widely published expert on Parkinson’s disease management, deep brain stimulation, and neuroprotective strategies. Co-author of "Parkinson's Treatment: 10 Secrets to a Happier Life."

Dr. Irene Hegeman Richard, MD Professor of Neurology, University of Rochester Medical Center. Specialist in movement disorders with a research focus on non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, including depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline.

Dr. Joseph Jankovic, MD Founder and Director, Parkinson’s Disease Center and Movement Disorders Clinic, Baylor College of Medicine. International authority on Parkinson’s disease and dystonia, with over 1,000 publications on clinical trials, pharmacology, and long-term management of motor complications.

Dr. Rajesh Pahwa, MD Professor of Neurology and Director of the Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder Center at the University of Kansas Medical Center. Principal investigator in numerous Parkinson’s disease clinical trials involving selegiline, rasagiline, and other early-intervention therapies.

Dr. Susan H. Fox, MB ChB, MRCP(UK), PhD Associate Professor of Neurology, University of Toronto; Staff Neurologist at Toronto Western Hospital. Researcher in Parkinson’s disease pharmacotherapy, including MAO-B inhibitors and dopamine agonists, with numerous contributions to treatment guidelines.

(Updated at Sep 26 / 2025)