Motor Fluctuations in Parkinsons Disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurological disorder that affects movement, muscle control, and balance. While tremors, stiffness, and slowness of movement are the hallmark symptoms, another important phenomenon that significantly impacts quality of life is motor fluctuations. These fluctuations are often complex, involving both the timing of symptoms and the body’s response to treatment. Understanding what motor fluctuations are, why they happen, and how they are managed is critical for patients, caregivers, and healthcare professionals.

What Is a Motor Fluctuation?

Motor fluctuations refer to the variations in a patient’s ability to move over the course of the day as a result of changes in the effectiveness of medication — most commonly levodopa, the mainstay treatment for Parkinson’s disease. Patients describe these fluctuations as periods when their medication is “working” (called ON time) and periods when the medication wears off and their symptoms re-emerge or worsen (called OFF time).

In simple terms, motor fluctuations are the difference between moments of improved mobility and moments of limited mobility caused by the inconsistency of dopamine replacement therapy in the brain. They are not present in the earliest stages of Parkinson’s but often appear after several years of treatment, as the disease progresses and the brain’s natural ability to regulate dopamine decreases.

Types of motor fluctuations include:

- Wearing-off: Symptoms return before the next dose of medication is due.

- On–off fluctuations: Sudden, unpredictable changes between mobility and immobility.

- Dose failures or delayed ON: When medication takes longer to act or does not work at all.

These fluctuations can be highly disruptive, making daily life unpredictable and causing difficulties with movement, work, and social interactions.

What Is the Origin of Motor Fluctuations in Parkinson’s Disease?

The origins of motor fluctuations lie in the underlying neurobiology of Parkinson’s disease and the way treatments interact with the degenerating nervous system.

- Dopamine neuron loss: In Parkinson’s disease, dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra progressively die. These neurons normally store and release dopamine in a steady manner, smoothing out brain signaling for coordinated movement.

- Levodopa pharmacokinetics: Levodopa, the most effective drug for Parkinson’s, temporarily restores dopamine levels in the brain. However, as neuronal loss continues, the brain loses its capacity to store dopamine. This means that the effect of each dose of levodopa becomes shorter and more erratic, leading to pulsatile dopamine stimulation.

- Receptor sensitivity changes: Over time, dopamine receptors in the striatum become more sensitive to fluctuating dopamine levels. This heightened sensitivity contributes not only to motor fluctuations but also to dyskinesias (involuntary movements).

- Gut absorption factors: Variations in how levodopa is absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract — delays, competition with dietary protein, or erratic emptying of the stomach — also contribute to inconsistent drug availability.

Thus, motor fluctuations are essentially the result of a mismatch between a continuous disease process (progressive dopamine loss) and the intermittent way in which levodopa restores dopamine in the brain.

Stage 1 of Parkinson’s Disease

To understand when motor fluctuations typically appear, it is important to look at the stages of Parkinson’s disease progression. The Hoehn and Yahr scale is a commonly used tool to classify stages of Parkinson’s:

- Stage 1: The disease is mild, symptoms are unilateral (affecting only one side of the body), and they do not interfere significantly with daily activities. The person may have a slight tremor, stiffness, or changes in posture, but they remain fully functional.

At this stage, motor fluctuations are not typically seen because the brain still has enough dopaminergic capacity to buffer dopamine levels. Patients often respond consistently to low doses of levodopa or other medications.

Motor fluctuations generally emerge several years after diagnosis, often in stages 2 or 3, as the disease progresses and long-term dopaminergic therapy begins to lose its smooth effectiveness.

How Do You Treat Motor Fluctuations in Parkinson’s Disease?

Treatment of motor fluctuations involves a multifaceted approach aimed at smoothing out dopamine delivery and reducing the variability of symptoms. Management must be individualized, depending on the type and severity of fluctuations, the patient’s age, and overall health.

Medication Adjustments

- More frequent dosing of levodopa: Smaller, more frequent doses can help reduce “wearing-off” periods.

- Controlled-release formulations: Extended-release forms of levodopa, or combination drugs like levodopa/carbidopa/entacapone, provide steadier dopamine levels.

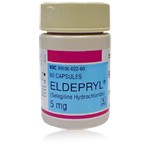

- Adjunctive medications: Drugs that prolong the effect of levodopa, such as COMT inhibitors (entacapone, opicapone) or MAO-B inhibitors (rasagiline, selegiline/Eldepryl), are commonly used to reduce OFF time.

Dopamine Agonists

Medications like pramipexole, ropinirole, or rotigotine mimic dopamine and stimulate dopamine receptors directly. They can smooth fluctuations and reduce reliance on levodopa, especially in younger patients.

Advanced Therapies

- Apomorphine injections or infusions: Provide rapid rescue from OFF periods.

- Levodopa-carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG): A pump delivers continuous levodopa directly into the small intestine, bypassing erratic stomach absorption.

- Deep brain stimulation (DBS): Surgical implantation of electrodes into specific brain regions can reduce motor fluctuations and dyskinesias in appropriate candidates.

Lifestyle and Diet

Protein management (timing protein intake away from levodopa dosing), regular exercise, and stress reduction can help optimize treatment effectiveness.

The overall goal is to restore more continuous dopaminergic stimulation, reducing the peaks and valleys that cause motor fluctuations.

The Role of Eldepryl in the Treatment of Motor Fluctuations

Eldepryl (generic name selegiline) is a monoamine oxidase-B (MAO-B) inhibitor used in the management of Parkinson’s disease. Its role in treating motor fluctuations is important, though often supportive rather than primary.

Mechanism of Action

MAO-B is an enzyme in the brain that breaks down dopamine. By inhibiting this enzyme, selegiline increases and prolongs the availability of dopamine, enhancing the effect of levodopa. This leads to a more consistent dopamine supply between doses and helps reduce OFF periods.

Clinical Use

- In early Parkinson’s disease, selegiline may be used as a monotherapy, offering mild symptomatic relief and possibly delaying the need for levodopa.

- In advanced Parkinson’s disease with motor fluctuations, Eldepryl is often added to levodopa therapy to reduce wearing-off and prolong ON time.

Benefits and Limitations

Eldepryl can modestly improve symptom control and smooth out fluctuations, but it does not eliminate them entirely. Additionally, its effect may diminish over time as the disease advances. Patients may also experience side effects such as insomnia, nausea, or interactions with other medications.

Despite these limitations, Eldepryl remains a valuable adjunct in managing motor fluctuations, particularly when patients begin to experience shorter response durations to levodopa.

Looking Ahead: Research and Future Directions

Motor fluctuations highlight the challenge of managing a chronic, progressive neurodegenerative disease with medications that were never designed to replicate the brain’s natural dopamine regulation perfectly. Current research is focused on:

- Continuous drug delivery systems (patches, pumps, novel oral formulations).

- New pharmacological strategies, including adenosine receptor antagonists and glutamate modulators.

- Cell-based and gene therapies aimed at restoring dopamine-producing neurons or modulating pathways beyond dopamine.

These approaches seek to provide smoother, more physiologic treatment, reducing the burden of fluctuations.

Conclusion

Motor fluctuations are a major complication of long-term Parkinson’s disease management. They arise from the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons, combined with the limitations of intermittent levodopa therapy. Patients experience cycles of mobility (ON periods) and immobility (OFF periods), often disrupting daily life.

Treatment requires a combination of medication adjustments, adjunct therapies like MAO-B inhibitors (including Eldepryl), and sometimes advanced interventions such as intestinal gel infusion or deep brain stimulation. Understanding motor fluctuations and addressing them proactively can greatly improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

While stage 1 of Parkinson’s disease is generally mild and free from fluctuations, these complications tend to develop in later stages, emphasizing the need for long-term planning and flexible management strategies.

Ultimately, the management of motor fluctuations reflects the broader challenge of Parkinson’s care: maintaining independence and quality of life in the face of a progressive disorder. With continued research and therapeutic innovation, the outlook for patients experiencing motor fluctuations continues to improve.

(Updated at Aug 24 / 2025)